Author: Umang Dayal

Physical AI succeeds not only because of larger models, but also because of richer, synchronized multisensor data streams.

There has been a quiet but decisive shift from single-modality perception, often vision-only systems, to integrated multimodal intelligence. But they are no longer enough. A robot that sees a cup may still drop it if it cannot feel the grip. A vehicle that detects a pedestrian visually may struggle in fog without radar confirmation. A drone that estimates position visually may drift without inertial stabilization.

Physical intelligence emerges at the intersection of perception channels, and multisensor fusion binds them together. In this article, we will discuss how multisensor fusion data underpins Physical AI systems, why it matters, how it works in practice, the engineering trade-offs involved, and what it means for teams building embodied intelligence in the real world.

What Is Multisensor Fusion in the Context of Physical AI?

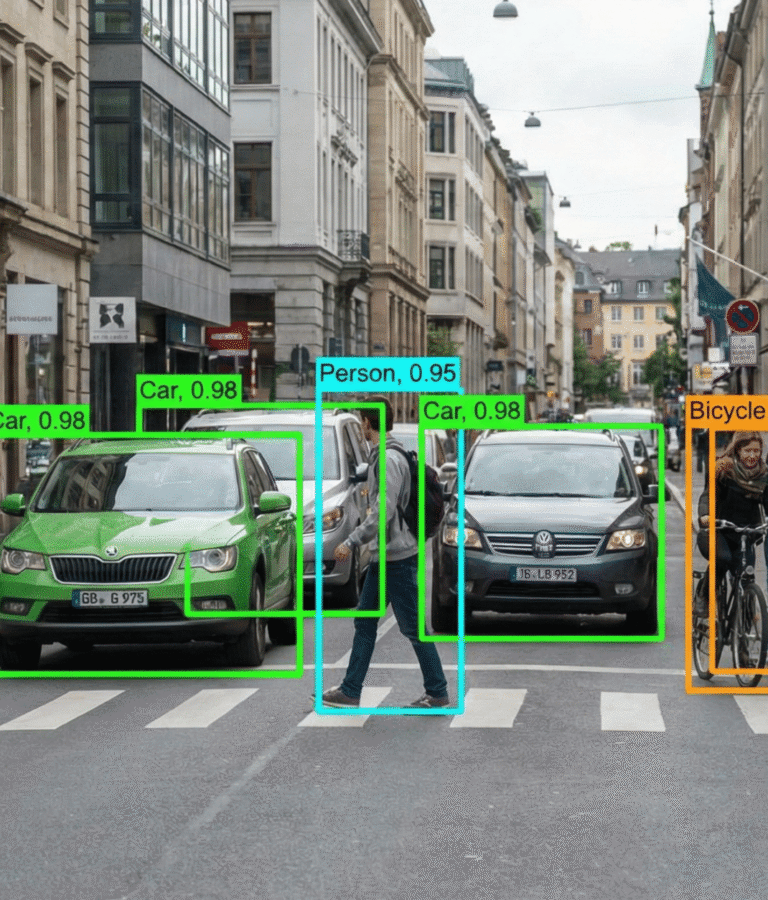

Multisensor fusion combines heterogeneous sensor streams into a unified, structured representation of the world.

Fusion is not merely the act of stacking data together. It is not dumping LiDAR point clouds next to RGB frames and hoping a neural network “figures it out.” Effective fusion involves synchronization, spatial alignment, context modeling, and uncertainty estimation. It requires decisions about when to trust one modality over another, and when to reconcile conflicts between them.

In a warehouse robot, for example, vision may indicate that a package is aligned. Force sensors might disagree, detecting uneven contact. The system has to decide: is the visual signal misleading due to glare? Or is the force reading noisy? A context-aware fusion architecture weighs these inputs, often dynamically.

So fusion, in practice, is closer to structured integration than simple aggregation. It aims to create a coherent internal state representation from fragmented sensory evidence.

Types of Sensors in Physical AI Systems

Each sensor modality contributes a partial truth. Alone, it is incomplete. Together, they begin to approximate operational completeness.

Visual Sensors

RGB cameras remain foundational. They provide semantic information, object identity, boundaries, and textures. Depth cameras and stereo rigs add geometric understanding. Event cameras capture motion at microsecond granularity, useful in high-speed environments. But vision struggles in low light, glare, fog, or heavy dust. It can misinterpret reflections and cannot directly measure force or weight.

Tactile Sensors

Force and pressure sensors embedded in robotic grippers detect contact. Slip detection sensors recognize micro-movements between surfaces. Tactile arrays can measure distributed pressure patterns. Vision might tell a robot that it is holding a ceramic mug. Tactile sensors reveal whether the grip is secure. Without that feedback, dropping fragile objects becomes almost inevitable.

Proprioceptive Sensors

Joint encoders and torque sensors measure internal state: joint angles, velocities, and motor effort. They help a robot understand its own posture and movement. Slight encoder drift can accumulate into noticeable positioning errors. Fusion between vision and proprioception often corrects such drift.

Inertial Sensors (IMUs)

Gyroscopes and accelerometers measure orientation and acceleration. They are critical for drones, humanoids, and autonomous vehicles. IMUs provide high-frequency motion signals that cameras cannot match. However, inertial sensors drift over time. They need external references, often vision or GPS, to recalibrate.

Environmental Sensors

LiDAR, radar, and ultrasonic sensors measure distance and object presence. Radar can operate in poor visibility where cameras struggle. LiDAR generates precise 3D geometry. Ultrasonic sensors assist in short-range detection. Each has strengths and blind spots. LiDAR may struggle in heavy rain. Radar offers less detailed geometry. Ultrasonic sensors have a limited range.

Audio Sensors

In advanced embodied systems, microphones detect contextual cues: machinery noise, human speech, and environmental hazards. Audio can indicate anomalies before visual signals become apparent. Individually, each modality provides a slice of reality. Fusion weaves these slices into a more stable picture. It does not eliminate uncertainty, but it reduces blind spots.

Why Physical AI Depends on Multisensor Fusion

Handling Real-World Uncertainty

The physical world is messy. Lighting changes between morning and afternoon. Warehouse floors accumulate dust. Outdoor vehicles encounter rain, fog, and snow. Sensors degrade. Vision-only systems may perform impressively in curated demos. Under fluorescent glare or heavy fog, they may falter. Sensor noise is not theoretical; it is a daily operational reality.

When vision confidence drops, radar might still detect motion. When LiDAR returns are sparse due to reflective surfaces, cameras may fill the gap. When tactile sensors detect unexpected force, the system can halt movement even if vision appears normal.

Fusion architectures that estimate uncertainty across modalities appear more resilient. They do not treat each input equally at all times. Instead, they dynamically reweight signals depending on environmental context. Physical AI without fusion is like driving with one eye closed. It may work in ideal conditions. It is unlikely to scale safely.

Grounding AI in Physical Interaction

Consider a robotic arm assembling small mechanical parts. Vision identifies the bolt. Proprioception confirms arm position. Tactile sensors detect contact pressure. IMU data ensures stability during motion. Fusion integrates these signals to determine whether to tighten further or stop.

Without tactile feedback, tightening might overshoot. Without proprioception, alignment errors accumulate. Without vision, object identification becomes guesswork. Physical intelligence emerges from grounded interaction. It is not abstract reasoning alone. It is embodied reasoning, anchored in sensory feedback.

Fusion Architectures in Physical AI Systems

Fusion is not a single algorithm. It is a design choice that influences model architecture, latency, interpretability, and safety.

Early Fusion

Early fusion combines raw sensor data at the input stage. Camera frames, depth maps, and LiDAR projections might be concatenated before entering a neural network.

But raw concatenation increases dimensionality significantly. Synchronization becomes tricky. Minor timestamp misalignment can corrupt learning. And raw fusion may dilute modality-specific nuances.

Late Fusion

Late fusion processes each modality independently, merging outputs at the decision level. A perception module might output object detections from vision. A separate module estimates distances from LiDAR. A fusion layer reconciles final predictions.

This design is modular. It allows teams to iterate on components independently. In regulated industries, modularity can be attractive. Yet, late fusion may lose cross-modal feature learning. The system might miss subtle correlations between texture and geometry that only joint representations capture.

Hybrid / Hierarchical Fusion

Hybrid approaches attempt a middle ground. They combine modalities at intermediate layers. Cross-attention mechanisms align features. Latent space representations allow modalities to influence one another without fully merging raw inputs.

This layered design appears to balance specialization and integration. Vision features inform depth interpretation. Tactile signals refine object pose estimation. However, complexity grows. Debugging becomes harder. Interpretability can suffer if alignment mechanisms are opaque.

End-to-End Multimodal Policies

An emerging approach maps sensor streams directly to actions. Unified models ingest multimodal inputs and output control commands.

The benefits are compelling. Reduced pipeline fragmentation. Potentially smoother integration between perception and control. Still, risks exist. Interpretability decreases. Overfitting to specific sensor configurations may occur. Safety validation becomes more challenging when decisions are deeply entangled across modalities.

Data Engineering Challenges in Multisensor Fusion

Behind every functioning physical AI system lies an immense data engineering effort. The glamorous part is model training. The harder part is making data usable.

Temporal Synchronization

Sensors operate at different frequencies. Cameras may run at 30 frames per second. IMUs can exceed 200 Hz. LiDAR might rotate at 10 Hz. If timestamps drift, fusion degrades. Even a millisecond misalignment can distort high-speed control.

Sensor drift and latency alignment require careful engineering. Timestamp normalization frameworks and hardware synchronization protocols become essential. Without them, training data contains hidden inconsistencies.

Spatial Calibration

Each sensor has intrinsic and extrinsic parameters. Miscalibrated coordinate frames create spatial errors. A LiDAR point cloud slightly misaligned with camera frames leads to incorrect object localization. Calibration must account for vibration, temperature changes, and mechanical wear. Cross-sensor coordinate transformation pipelines are not one-time tasks. They require periodic validation.

Data Volume and Storage

Multisensor systems generate enormous data volumes. High-resolution video combined with dense point clouds and high-frequency IMU streams quickly exceeds terabytes.

Edge processing reduces transmission load. But real-time constraints limit compression options. Teams must decide what to store, what to discard, and what to summarize. Storage strategies directly influence retraining capability.

Annotation Complexity

Labeling across modalities is demanding. Annotators may need to mark 3D bounding boxes in point clouds, align them with 2D frames, and verify consistency across timestamps.

Cross-modal consistency is not trivial. A pedestrian visible in a camera frame must align with corresponding LiDAR returns. Generating ground truth in 3D space often requires specialized tooling and experienced teams. Annotation quality significantly influences model reliability.

Simulation-to-Real Gap

Simulation accelerates data generation. Synthetic data allows edge-case modeling. Yet synthetic sensors often lack realistic noise. Sensor noise modeling becomes crucial. Domain randomization helps, but cannot perfectly capture environmental unpredictability. Bridging simulation and reality remains an ongoing challenge. Fusion complicates it further because each modality introduces its own realism requirements.

Strategic Implications for AI Teams

Multisensor fusion is not just a technical problem. It is a strategic one.

Data-Centric Development Over Model-Centric Scaling

Scaling parameters alone may yield diminishing returns. Fusion-aware dataset design often delivers more tangible gains. Teams should prioritize multimodal validation protocols. Does performance degrade gracefully when one sensor fails? Is the model over-reliant on a dominant modality? Data diversity across environments, lighting, weather, and hardware configurations matters more than marginal architecture tweaks.

Infrastructure Investment Priorities

Sensor stack standardization reduces integration friction. Synchronization tooling ensures consistent training data. Real-time inference hardware supports latency constraints. Underinvesting in infrastructure can undermine model progress. High-performing models trained on poorly synchronized data may behave unpredictably in deployment.

Building Competitive Advantage

Proprietary multimodal datasets become defensible assets. Closed-loop feedback data, collected from deployed systems, enables continuous refinement. Real-world operational data pipelines are difficult to replicate. They require coordinated engineering, field testing, and annotation workflows. Competitive advantage may increasingly lie in data orchestration rather than model novelty.

Conclusion

The next generation of breakthroughs in robotics, autonomous vehicles, and embodied systems may not come from simply scaling architectures upward. They are likely to emerge from smarter integration, systems that understand not just what they see, but what they feel, how they move, and how the environment responds.

Physical AI is still evolving. Its foundations are being built now, in data pipelines, annotation workflows, sensor stacks, and fusion frameworks. The teams that treat multisensor fusion as a core capability rather than an afterthought will probably be the ones that move from impressive demos to dependable deployment.

How DDD Can Help

Digital Divide Data (DDD) delivers high-quality multisensor fusion services that combine camera, LiDAR, radar, and other sensor data into unified training datasets. By synchronizing and annotating multimodal inputs, DDD helps computer vision systems achieve reliable perception, improved accuracy, and real-world dependability.

As a global leader in computer vision data services, DDD enables AI systems to interpret the world through integrated sensor data. Its multisensor fusion services combine human expertise, structured quality frameworks, and secure infrastructure to deliver production-ready datasets for complex AI applications.

Talk to our expert and build smarter Physical AI systems with precision-engineered multisensor fusion data from DDD.

References

Salian, I. (2025, August 11). NVIDIA Research shapes physical AI. NVIDIA Blog.

Qian, H., Wang, M., Zhu, M., & Wang, H. (2025). A review of multi-sensor fusion in autonomous driving. Sensors, 25(19), 6033. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196033

Hwang, J.-J., Xu, R., Lin, H., Hung, W.-C., Ji, J., Choi, K., Huang, D., He, T., Covington, P., Sapp, B., Zhou, Y., Guo, J., Anguelov, D., & Tan, M. (2025). EMMA: End-to-end multimodal model for autonomous driving (arXiv:2410.23262). arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.23262

Din, M. U., Akram, W., Saad Saoud, L., Rosell, J., & Hussain, I. (2026). Multimodal fusion with vision-language-action models for robotic manipulation: A systematic review. Information Fusion, 129, 104062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2025.104062

FAQs

- How does multisensor fusion impact energy consumption in embedded robotics?

Fusion models may increase computational load, especially when processing high-frequency streams like LiDAR and IMU data. Efficient architectures and edge accelerators are often required to balance perception accuracy with battery constraints. - Can multisensor fusion work with low-cost hardware?

Yes, but trade-offs are likely. Lower-resolution sensors or reduced calibration precision may affect performance. Intelligent weighting and redundancy strategies can partially compensate. - How often should sensor calibration be updated in deployed systems?

It depends on mechanical stress, environmental exposure, and operational intensity. Industrial robots may require periodic recalibration schedules, while autonomous vehicles may rely on continuous self-calibration algorithms. - Is fusion necessary for all physical AI applications?

Not always. Controlled environments with stable lighting and limited variability may operate effectively with fewer modalities. However, open-world deployments typically benefit from multimodal redundancy.