Author: Umang Dayal

The promise of automation has always been efficiency. Fewer delays, faster decisions, reduced human error. And yet, as these systems become more autonomous, something interesting happens: risk does not disappear; it migrates.

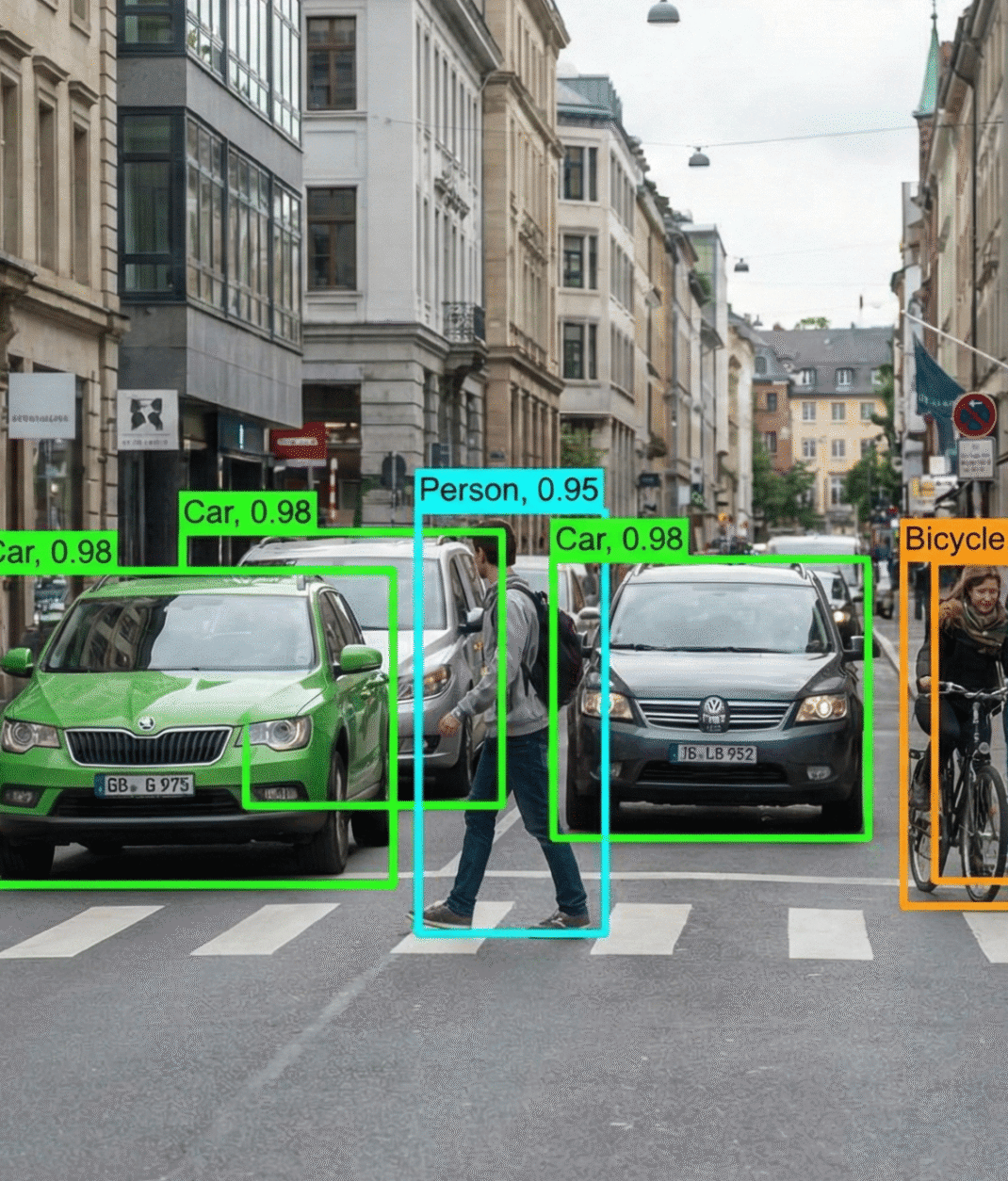

Instead of a distracted operator missing a signal, we may now face a model that misinterprets glare on a wet road. Instead of a fatigued technician overlooking a defect, we might have a neural network misclassifying an unusual pattern it never encountered in training data for AV.

There’s also a persistent illusion in the market: the idea of “fully autonomous” systems. The marketing language often suggests a clean break from human dependency. But in practice, what emerges is layered oversight, remote support teams, escalation protocols, human review panels, and more.

Enterprises must document who intervenes, how decisions are recorded, and what safeguards are in place when models behave unpredictably. Boards ask uncomfortable questions about liability. Insurers scrutinize safety architecture. All of these points toward a conclusion that might feel less glamorous but far more grounded:

In safety-critical environments, Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) computer vision is not a fallback mechanism; it is a structural requirement for resilience, accountability, and trust. In this detailed guide, we will explore Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) computer vision for safety-critical systems, develop effective architectures, and establish robust workflows.

What Is Human-in-the-Loop in Computer Vision?

“Human-in-the-Loop” can mean different things depending on who you ask. For some, it’s about annotation, humans labeling bounding boxes and segmentation masks. For others, it’s about a remote operator taking control of a vehicle during edge cases. In reality, HITL spans the entire lifecycle of a vision system.

Human involvement can be embedded within:

Data labeling and validation – Annotators refining datasets, resolving ambiguous cases, and identifying mislabeled samples.

Model training and retraining – Subject matter experts reviewing outputs, flagging systematic errors, guiding retraining cycles.

Real-time inference oversight – Operators reviewing low-confidence predictions or intervening when anomalies occur.

Post-deployment monitoring – Analysts auditing performance logs, reviewing incidents, and adjusting thresholds.

Why Vision Systems Require Special Attention

Vision systems operate in messy environments. Unlike structured databases, the visual world is unpredictable. Perception errors are often high-dimensional. A small shadow may alter classification confidence. A slightly altered angle can change bounding box accuracy. A sticker on a stop sign might confuse detection.

Edge cases are not theoretical; they’re daily occurrences. Consider:

- A construction worker wearing reflective gear that obscures their silhouette.

- A pedestrian pushing a bicycle across a road at dusk.

- Medical imagery containing artifacts from older equipment models.

Visual ambiguity complicates matters further. Is that a fallen branch on the highway or just a dark patch? Is a cluster of pixels noise or an early-stage anomaly in a scan?

Human judgment, imperfect as it is, excels at contextual interpretation. Vision models excel at pattern recognition at scale. In safety-critical systems, one without the other appears incomplete.

Why Safety-Critical Systems Cannot Rely on Full Autonomy

The Nature of Safety-Critical Environments

In a content moderation system, a false positive may frustrate a user. In a surgical assistance system, a false positive could mislead a clinician. The difference is not incremental; it’s structural. When failure consequences are severe, explainability becomes essential. Stakeholders will ask: What happened? Why did the system decide this? Could it have been prevented?

Without a human oversight layer, answers may be limited to probability distributions and confidence scores, insufficient for legal or operational review.

The Automation Paradox

There’s an uncomfortable phenomenon sometimes described as the automation paradox. As systems become more automated, human operators intervene less frequently. Then, when something goes wrong, often something rare and unusual, the human is suddenly required to take control under pressure.

Imagine a remote vehicle support operator overseeing dozens of vehicles. Most of the time, the dashboard remains calm. Suddenly, a complex intersection scenario triggers an escalation. The operator has seconds to assess camera feeds, sensor overlays, and context.

The irony? The more reliable the system appears, the less prepared the human may be for intervention. That tension suggests full autonomy may not simply be a technical challenge; it’s a human systems design challenge.

Trust, Liability, and Accountability

Who is responsible when perception fails?

In regulated markets, accountability frameworks increasingly require verifiable oversight layers. Enterprises must demonstrate not just that a system performs well in benchmarks, but that safeguards exist when it does not. Human oversight becomes both a technical mechanism and a legal one. It provides a checkpoint. A record. A place where responsibility can be meaningfully assigned. Without it, organizations may find themselves exposed, not only technically, but also reputationally and legally.

Where Humans Fit in the Vision Pipeline

Data-Centric HITL

Data is where many safety issues originate. A vision model trained predominantly on sunny weather may struggle in fog. A dataset lacking diversity may introduce bias in detection.

Human-in-the-loop at the data stage includes:

- Annotation quality control

- Edge-case identification

- Active learning loops

- Bias detection and correction

- Continuous dataset refinement

For example, annotators might notice that nighttime pedestrian images are underrepresented. Or that certain industrial defect types appear inconsistently labeled. Those observations feed directly into model improvement. Active learning systems can flag uncertain predictions and route them to expert reviewers. Over time, the dataset evolves, ideally reducing blind spots. Data-centric HITL may not feel dramatic, but it’s foundational.

Model Development HITL

An engineering team might notice that a system confuses scaffolding structures with human silhouettes. Instead of treating all errors equally, they categorize them. Confidence thresholds are particularly interesting. Set them too low, and the system rarely escalates, risking missed edge cases. Set them too high, and operators drown in alerts. Finding that balance often requires iterative human evaluation, not just statistical optimization.

Real-Time Operational HITL

In live environments, human escalation mechanisms become visible. Confidence-based routing may direct low-certainty detections to a monitoring center. An operator reviews video snippets and confirms or overrides decisions. Override mechanisms must be clear and accessible. If an industrial robot’s vision system detects a human in proximity, a supervisor should have immediate authority to pause operations. Designing these workflows requires clarity about response times, accountability, and documentation.

Post-Deployment HITL

No system remains static after deployment. Incident review boards analyze edge cases. Drift detection workflows flag performance degradation as environments change. Retraining cycles incorporate newly observed patterns. Safety audits and compliance documentation often rely on human interpretation of logs and events. In this sense, HITL extends far beyond the moment of decision; it becomes an ongoing governance process.

HITL Architectures for Safety-Critical Computer Vision

Confidence-Gated Architectures

In confidence-gated systems, the model outputs a probability score. Predictions below a defined threshold are escalated to human review. Dynamic thresholding may adjust based on context. For instance, in a low-risk warehouse zone, a slightly lower confidence threshold might be acceptable. Near hazardous materials, stricter thresholds apply. This approach appears straightforward but requires careful calibration. Over-escalation can overwhelm operators, and under-escalation can introduce risk.

Dual-Channel Systems

Dual-channel systems combine automated decision-making with parallel human validation streams. For example, an automated rail inspection system flags potential track anomalies. A human analyst reviews flagged images before maintenance crews are dispatched. Redundancy increases reliability, though it also increases operational cost. Enterprises must weigh efficiency against safety margins.

Supervisory Control Models

Here, humans monitor dashboards and intervene only under specific triggers. Visualization tools become critical. Operators need clear summaries, not dense technical overlays. Risk scoring, anomaly heatmaps, and simplified indicators help maintain situational awareness. A poorly designed interface may undermine even the most accurate model.

Designing Effective Human-in-the-Loop Workflows

Avoiding Cognitive Overload

Operators in control rooms already face information saturation. Introducing AI-generated alerts can amplify that burden. Interface clarity matters. Alerts should be prioritized. Context, timestamp, camera angle, and environmental conditions should be visible at a glance. Alarm fatigue is real. If too many low-risk alerts trigger, operators may begin ignoring them. Ironically, the system designed to enhance safety could erode it.

Operator Training & Skill Retention

Skill retention may require deliberate effort. Continuous simulation environments can expose operators to rare scenarios, black ice on roads, unexpected pedestrian behavior, and unusual equipment failures. Scenario-based drills keep intervention skills sharp. Otherwise, human oversight becomes nominal rather than functional.

Latency vs. Safety Tradeoffs

How fast must a human respond? Designing for controlled degradation, where a system transitions safely into a low-risk mode while awaiting human input, can mitigate time pressure. Full automation may still be justified in tightly constrained environments. The key is recognizing where that boundary lies.

How Digital Divide Data (DDD) Can Help

Building and maintaining Human-in-the-Loop computer vision systems isn’t just a technical challenge; it’s an operational one. It demands disciplined data workflows, rigorous quality control, and scalable human oversight. Digital Divide Data (DDD) helps enterprises structure this foundation. From high-precision, domain-specific annotation with multi-layer QA to edge-case identification and bias detection, DDD designs processes that surface ambiguity early and reduce downstream risk.

As systems evolve, DDD supports active learning loops, retraining workflows, and compliance-ready documentation that meets regulatory expectations. For real-time escalation models, DDD can also manage trained review teams aligned to defined intervention protocols. In effect, DDD doesn’t just supply labeled data; it builds the structured human oversight that safety-critical AI systems depend on.

Conclusion

The real question isn’t whether AI can operate autonomously. In many environments, it already does. The better question is where autonomy should pause, and how humans are positioned when it does. Human-in-the-Loop systems acknowledge something simple but important: uncertainty is inevitable. Rather than pretending it can be eliminated, they design for it. They create checkpoints, escalation paths, audit trails, and shared responsibility between machines and people.

For enterprises operating in regulated, high-risk industries, this approach is increasingly non-negotiable. Compliance expectations are tightening. Liability frameworks are evolving. Stakeholders want proof that safeguards exist, not just performance metrics.

The future of safety-critical AI will not be defined by removing humans from the loop. It will be defined by placing them intelligently within it, where judgment, context, and responsibility still matter most.

Talk to our experts to build safer vision systems with structured human oversight.

References

European Parliament & Council of the European Union. (2024). Regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). Official Journal of the European Union.

Waymo Research. (2024). Advancements in end-to-end multimodal models for autonomous driving systems. Waymo LLC.

NVIDIA Corporation. (2024). Designing human-in-the-loop AI systems for real-time decision environments. NVIDIA Developer Blog.

European Commission. (2024). High-risk AI systems and human oversight requirements under the EU digital strategy. Publications Office of the European Union.

FAQs

Is Human-in-the-Loop always required for safety-critical computer vision systems?

In most regulated or high-risk environments, some form of human oversight is typically expected, though its depth varies by use case.

Does adding humans to the loop significantly reduce efficiency?

When properly calibrated, HITL usually targets only high-uncertainty cases, limiting impact on overall efficiency.

How do organizations decide which decisions should be escalated to humans?

Escalation thresholds are generally defined based on risk severity, confidence scores, and regulatory exposure.

What are the highest hidden costs of Human-in-the-Loop systems?

Ongoing training, interface optimization, quality control management, and compliance documentation often represent the highest hidden costs.