By Umang Dayal

July 29, 2025

Computer vision can identify and classify objects within an image, and has long been a fundamental task. Traditional image classification approaches focus on assigning a single label to an image, assuming that each visual sample belongs to just one category. However, real-world images are rarely so simple. A photo might simultaneously contain a person, a bicycle, a road, and a helmet.

This complexity introduces the need for multi-label image classification (MLIC), where models predict multiple relevant labels for a single image. MLIC enables systems to interpret scenes with nuanced semantics, reflecting how humans perceive and understand visual content.

This blog explores multi-label image classification, focusing on key challenges, major techniques, and real-world applications.

Major Challenges in Multi-Label Image Classification

Multi-label image classification presents a unique set of obstacles that distinguish it from single-label classification tasks. These challenges span data representation, model design, training complexity, and deployment constraints. Addressing them requires a deep understanding of how multiple semantic labels interact, how they are distributed, and how visual and contextual cues can be effectively modeled. Below, we examine six of the most pressing issues.

High-Dimensional and Sparse Label Space

As the number of possible labels increases, the label space becomes exponentially large and inherently sparse. Unlike single-label tasks with mutually exclusive classes, multi-label problems must account for every possible combination of labels. This often leads to situations where many label combinations are underrepresented or absent altogether in the training data. Additionally, some labels occur frequently while others appear only rarely, leading to class imbalance. These conditions make it challenging for models to learn meaningful patterns without overfitting to dominant classes or overlooking rare yet important ones.

Label Dependencies and Co-occurrence Complexity

In multi-label settings, labels are rarely independent. Certain objects often appear together in specific contexts. For example, a “car” is likely to co-occur with “road” and “traffic light” in urban scenes. Capturing these dependencies is crucial for improving predictive performance. However, relying too heavily on co-occurrence statistics can be misleading, especially in edge cases or uncommon contexts. Static label graphs, which model these dependencies globally, may fail to generalize when scene-specific relationships differ from global trends. Effective multi-label classification must account for both general label interactions and context-specific deviations.

Spatial and Semantic Misalignment

Another major challenge arises from the spatial distribution of labels within an image. In multi-object scenes, different labels often correspond to distinct spatial regions that may or may not overlap. For example, in a street scene, “pedestrian” and “bicycle” might be close together, while “sky” and “building” occupy completely different areas. Without mechanisms to attend to label-specific regions, models may blur or miss important details. Semantic misalignment also occurs when visual features are ambiguous or shared across categories, requiring models to differentiate subtle contextual cues.

Data Scarcity and Annotation Cost

Multi-label datasets are significantly harder to annotate than their single-label counterparts. Each image may require multiple judgments, increasing the cognitive load and time required for human annotators. In some domains, such as medical or aerial imaging, data annotations must come from experts, further escalating costs. Noisy, incomplete, or inconsistent labels are common, and they degrade model performance. As a result, many real-world datasets remain limited in scale or quality, constraining the potential of supervised learning approaches.

Overfitting on Co-occurrence Statistics

While label co-occurrence can help guide predictions, it also poses the risk of overfitting. When models learn to rely excessively on frequent label combinations, they may neglect visual cues entirely. For instance, if “helmet” is usually seen with “bicycle,” a model might incorrectly predict “helmet” even when it is absent, simply because “bicycle” is present. This reduces robustness and generalization, especially in test conditions where familiar co-occurrence patterns are violated. Disentangling visual features from statistical dependencies is essential for developing resilient multi-label classifiers.

Scalability and Real-Time Deployment Issues

Multi-label models often have larger architectures and require more computational resources than single-label ones. The need to output and evaluate predictions over many labels increases memory and inference time, which can be problematic for real-time or edge deployments. In applications like autonomous driving or mobile content moderation, latency and resource usage are critical constraints. Compressing models without sacrificing accuracy and designing efficient prediction pipelines remains a persistent challenge for practitioners working at scale.

Multi-Label Image Classification Techniques

Recent advancements in multi-label image classification have focused on addressing the fundamental challenges of label dependency modeling, data efficiency, semantic representation, and computational scalability.

Graph-Based Label Dependency Modeling

Modeling relationships among labels is central to improving MLIC performance. Traditional models often assume label independence, which limits their ability to understand structured co-occurrence patterns. Graph-based techniques have emerged to address this by explicitly representing and learning inter-label dependencies.

One of the notable contributions is Scene-Aware Label Graph Learning, which constructs dynamic graphs conditioned on the type of scene in the image. Rather than using a global, static label graph, the model adjusts its label relationship structure based on the visual context. This allows it to more accurately capture context-specific dependencies, such as recognizing that “snow” and “mountain” co-occur in alpine settings, while “building” and “car” co-occur in urban ones.

Multi-layered dynamic graphs have further advanced this concept by modeling label interactions at different semantic and spatial scales. These architectures allow label representations to evolve through multiple graph reasoning layers, improving the model’s ability to handle label sparsity and long-tail distributions.

Contrastive and Probabilistic Learning

Another promising direction has been the integration of contrastive learning with probabilistic representations. The ProbMCL framework (2024) combines supervised contrastive loss with a mixture density network to model uncertainty and capture multi-modal label distributions. This approach enables the model to learn nuanced inter-label relationships by pulling similar samples closer in the latent space, while accounting for uncertainty in label presence.

These techniques are particularly effective in settings with limited or noisy annotations. By leveraging representation-level similarity rather than raw label agreement, they help improve robustness and generalization, especially in domains with subtle or overlapping label semantics.

CAM and GCN Fusion Networks

Combining spatial attention with structural reasoning has also gained traction. Architectures that merge Class Activation Maps (CAMs) with Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) aim to align visual cues with label graphs. The idea is to localize features corresponding to each label via CAMs and then propagate label dependencies using GCNs.

These hybrid models can simultaneously encode spatial alignment (through CAM) and relational reasoning (through GCN), making them particularly effective in complex scenes with multiple interacting objects. This fusion helps models move beyond purely appearance-based recognition and consider the broader context of how objects co-occur spatially and semantically.

Prompt Tuning and Token Attention

Inspired by advances in natural language processing, prompt tuning has been adapted for visual classification tasks. Recent research on correlative and discriminative label grouping introduces a method that constructs soft prompts for label tokens, allowing the model to better differentiate between commonly co-occurring but semantically distinct labels.

By grouping labels based on both their correlation and discriminative attributes, the model avoids overfitting to frequent label combinations. This strategy enhances the model’s ability to learn label-specific features and maintain prediction accuracy even in less common or conflicting label scenarios.

Reinforcement-Based Active Learning

Annotation efficiency is further enhanced through reinforcement-based active learning techniques. Instead of randomly sampling data for labeling, these methods use a reinforcement learning agent to select the most informative samples that are likely to improve model performance.

This active learning framework adapts over time, learning to prioritize images that represent edge cases, underrepresented labels, or ambiguous contexts. The result is a more label-efficient training pipeline that accelerates learning and reduces dependence on large annotated datasets.

Read more: 2D vs 3D Keypoint Detection: Detailed Comparison

Industry Applications for Multi-Label Image Classification

Multi-label image classification spans a wide range of industries where understanding complex scenes, recognizing multiple entities, or tagging images with rich semantic information is essential. As real-world datasets grow in volume and complexity, multi-label classification has become a foundational capability in commercial systems, healthcare diagnostics, autonomous navigation, and beyond. This section explores prominent application domains and how multi-label models are being deployed at scale.

E-commerce and Content Moderation

In e-commerce platforms, the ability to tag images with multiple product attributes is critical for search accuracy, filtering, and personalized recommendations. A single product image might need to be labeled with attributes such as “men’s”, “leather”, “brown”, “loafers”, and “formal”. Multi-label classification enables automatic tagging of such attributes from visual data, reducing manual labor and improving metadata consistency.

Content moderation platforms also benefit from MLIC by detecting multiple types of content violations in images, such as identifying the simultaneous presence of offensive symbols, nudity, and weapons. These systems must prioritize both speed and accuracy to operate in real-time and at scale, especially in user-generated content ecosystems.

Healthcare Diagnostics

Medical imaging is a domain where multi-label classification plays a vital role. An X-ray or MRI scan may reveal several co-occurring conditions, and detecting all of them is essential for a comprehensive diagnosis. For instance, in chest X-rays, a single image might show signs of pneumonia, enlarged heart, and pleural effusion simultaneously.

Multi-label models trained on datasets help radiologists by providing automated, explainable preliminary assessments. These models often incorporate uncertainty estimation and attention maps to enhance trust and usability. While deployment in clinical settings demands high accuracy and regulatory compliance, the use of MLIC reduces diagnostic oversight and accelerates reporting workflows.

Autonomous Systems

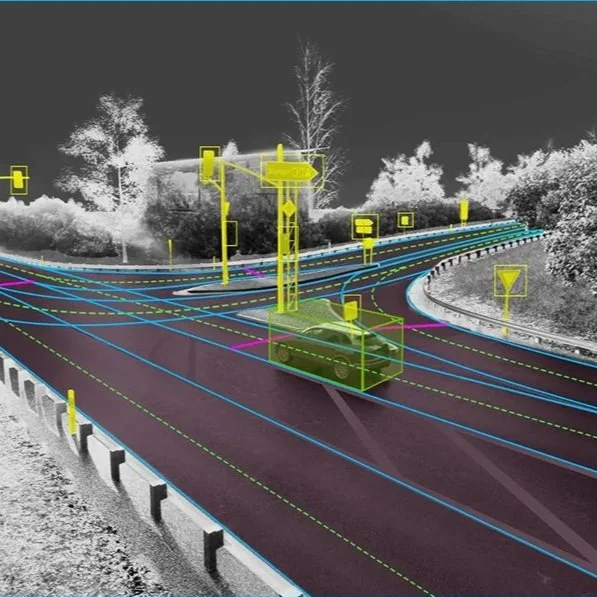

Self-driving vehicles, drones, and robotic systems rely heavily on perception models that can identify multiple objects and contextual elements in real time. A single street-level image may contain pedestrians, cyclists, vehicles, road signs, lane markings, and construction zones. All these elements must be detected and classified simultaneously to inform navigation and safety decisions.

Multi-label classifiers help these systems interpret rich visual scenes with high granularity, particularly when combined with object detectors or semantic segmentation networks. Edge deployment constraints make efficiency a key requirement, and recent lightweight architectures have made it feasible to run MLIC models on embedded hardware without significant performance trade-offs.

Satellite and Aerial Imaging

Remote sensing applications often require identifying multiple land use types, infrastructure elements, and environmental features from a single high-resolution satellite or aerial image. For example, a frame might simultaneously include “urban”, “water body”, “vegetation”, and “industrial facility” labels.

Multi-label classification aids in geospatial mapping, disaster assessment, agricultural monitoring, and military reconnaissance. Since such datasets often lack dense annotations and exhibit high class imbalance, models trained with techniques like pseudo-labeling and graph-based label correlation are particularly effective in this domain. Moreover, the ability to generalize across regions and seasons is crucial, further highlighting the importance of robust label dependency modeling.

Across all these industries, multi-label image classification offers a critical capability: the ability to extract a structured, multi-dimensional understanding from visual data. When deployed thoughtfully, these models reduce manual workload, enhance decision-making, and enable scalable automation. However, operational deployment also raises challenges, ranging from latency and throughput constraints to interpretability and fairness, which must be addressed through careful engineering and continual model refinement.

Read more: Mitigation Strategies for Bias in Facial Recognition Systems for Computer Vision

Conclusion

Multi-label image classification has emerged as a cornerstone of modern computer vision, enabling machines to interpret complex scenes and recognize multiple semantic concepts within a single image. Unlike single-label tasks, MLIC reflects the richness and ambiguity of the real world, making it indispensable in domains such as healthcare, autonomous systems, e-commerce, and geospatial analysis.

As we look to the future, multi-label classification is poised to benefit from broader shifts in machine learning: multimodal integration, foundation models, efficient graph learning, and a growing focus on fairness and accountability. These developments not only promise more accurate models but also more inclusive and ethically aware systems. Whether you’re developing for a mission-critical domain or scaling consumer applications, multi-label classification will continue to offer both technical challenges and transformative opportunities.

By embracing advanced techniques and grounding them in sound evaluation and ethical deployment, we can build MLIC systems that are not only powerful but also aligned with the complexity and diversity of the real world.

Scale your multi-label training datasets with precision and speed, partner with DDD

References:

Xie, S., Ding, G., & He, Y. (2024). ProbMCL: Probabilistic multi-label contrastive learning. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.01448

Xu, Y., Zhang, X., Sun, Z., & Hu, H. (2025). Correlative and discriminative label grouping for multi-label visual prompt tuning. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.09990

Zhang, Y., Zhou, F., & Yang, W. (2024). Classifier-guided CLIP distillation for unsupervised multi-label image classification. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.16873

Al-Maskari, A., Zhang, M., & Wang, S. (2025). Multi-label active reinforcement learning for efficient annotation under label imbalance. Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 240, 103939. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1077314225000748

Tarekegn, A. N., Adilina, D., Wu, H., & Lee, Y. (2024). A comprehensive survey of deep learning for multi-label learning. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.16549

OpenCV. (2025). Image classification in 2025: Insights and advances. OpenCV Blog. https://opencv.org/blog/image-classification/

SciSimple. (2025). Advancements in multimodal multi-label classification. SciSimple. https://scisimple.com/en/articles/2025-07-25-advancements-in-multimodal-multi-label-classification–akero11

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can I convert a multi-label problem into multiple binary classification tasks?

Yes, this approach is known as the Binary Relevance (BR) method. Each label is treated as a separate binary classification problem. While simple and scalable, it fails to model label dependencies, which are often critical in real-world applications. More advanced approaches like Classifier Chains or label graph models are preferred when label interdependence is important.

2. How does multi-label classification differ from multi-class classification technically?

In multi-class classification, an input is assigned to exactly one class from a set of mutually exclusive categories. In multi-label classification, an input can be assigned to multiple classes simultaneously. Technically, multi-class uses a softmax activation (with categorical cross-entropy loss), while multi-label uses a sigmoid activation per class (with binary cross-entropy or similar loss functions).

3. What data augmentation techniques are suitable for multi-label image classification?

Standard techniques like flipping, rotation, scaling, and cropping are generally effective. However, care must be taken with label-preserving augmentation to ensure that all annotated labels remain valid after transformation. Mixup and CutMix can be adapted, but may require label mixing strategies to preserve label semantics. Some pipelines also use region-aware augmentation to retain context for spatially localized labels.

4. Can I use object detection models for multi-label classification?

Object detection models like YOLO or Faster R-CNN detect individual object instances with bounding boxes and labels. While they can output multiple labels per image, their primary goal is instance detection rather than scene-level classification. For coarse or scene-level tagging, MLIC models are more efficient and often more appropriate, though hybrid systems combining both can offer rich annotations.

5. How do label noise and missing labels affect multi-label training?

Label noise and incompleteness are major issues in MLIC, particularly in weakly supervised or web-crawled datasets. Common mitigation strategies include:

-

Partial label learning, which allows learning from incomplete annotations

-

Robust loss functions like soft bootstrapping or asymmetric loss

-

Consistency regularization to stabilize predictions across augmentations